In the history of mankind, there is no culture that exists without having some form of music. Making music, and singing or dancing to its rhythm, is such a basic human instinct that even deaf people can not abandon the urge. Music - as the Turks say- is food for your soul. But may be the reason for why we are so addicted to it is because of what it does to our mind. Oliver Sacks -my favorite neurologist- claims in his book Musicophilia that he has Parkinson's patients who are free of the disease symptoms for the duration of the "mental music", i.e. the melody playing in your mind.

I am born in a culture where music is considered a necessity of life. Like many Turks, Kurds, Laz and Syriacs living on this land would agree, I can not imagine a day that passes without music. Inspired by a Turkish-Kurdish movie that I recently watched, Gelecek Uzun Sürer (Future Lasts Forever), I decided to collect as many sounds as possible during my trip to Eastern Turkey (street musicians, angry drivers, funny kids, a shepherd singing by himself, and so on). Equipped with my dear iPhone and with luck that "prefers the prepared mind", I spied on a collection of sounds that I am happy to share here.

I am born in a culture where music is considered a necessity of life. Like many Turks, Kurds, Laz and Syriacs living on this land would agree, I can not imagine a day that passes without music. Inspired by a Turkish-Kurdish movie that I recently watched, Gelecek Uzun Sürer (Future Lasts Forever), I decided to collect as many sounds as possible during my trip to Eastern Turkey (street musicians, angry drivers, funny kids, a shepherd singing by himself, and so on). Equipped with my dear iPhone and with luck that "prefers the prepared mind", I spied on a collection of sounds that I am happy to share here.

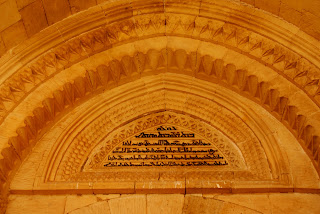

The first song is from Hasankeyf; I was up at the ruins of the 14th century Ulu Mosque when I heard a neyzen (reed flute player) playing ney in one of the dark, dusty rooms of the mosque. I sat by the door where sunset lights were streaking through, and silently listened to him play this enchanting melody.

Saçlarından bir tel aldım, haberin var mı yar yar? Haberin var mı?

Gözden ırak dilden uzak, ben seni sevmişem eyvah! Haberin var mı yar yar? Haberin var mı?

I took a strand of your hair, did you know my love? Did you know?

Far from the eye away from the word, I loved you, alas! Did you know my love? Did you know?

Here, listen to this "shy" to-be-artist Kurdish kid sing in Turkish.

The last song is from a nameless shepherd from Dara who was singing cheerfully to himself, waking us up from our long walk in the ancient city. Singing louder than the roosters around him and sounding like a morning alarm, he offers no mental music for Parkinson's patients. But who cares, right? As you are only free when you are singing freely...

Note: I prefer Saliho's version, but here is a "better" version of Haberin var mı yar yar?